Global Warming

It is just after 4 o’clock in the morning. I know this because I hear my son’s husky voice declare, “Omigod! I can’t believe it’s 4 to the 12!” (Me either. sigh)

He is looking at Aaron’s cell phone, at the clock that dominates the screen when the phone is charging: 4:12. I see his face lit only by the eerie greenish glow of the phone, his hair all bed-heady, his eyes animated and intensely focussed.

I should be annoyed. Sleep is the most precious thing in the life of a parent of young children, and I do not take kindly to being woken up if someone is not puking or if there isn’t, at the very least, a fire.

But Zeke catches my attention with what he says next, melting away any anger that might have been forming.

“Is the north getting cold again Mom?”

We’ve been talking about global warming. We heard a report on the radio about how scientists are struggling to find a way to preserve the polar bear species outside of their quickly disappearing natural habitat without placing them all on public display. The reporter said that, for the first time, it appeared quite possible that we would live in a world without polar bears within his lifetime. Zeke was riveted and concerned. He kept asking me how this could be happening. We watched some YouTube videos of polar bears sloshing through melting ice and swimming aimlessly through endless water, in search of something solid to stand on.

One chilly morning he leapt into my lap, threw his arms around my neck, and exclaimed,

“I have great news Mom! The earth is getting cold again! Look outside! The sky is all gray! I think it’s going to rain!”

He was so exhilarated by this miraculous development, by the extraordinary fact that a horrible tragedy appeared to be reversing course, that there was just no way that I could explain to him that the whole mess was a little more complicated than that. So I just hugged him close, told him I loved him, and made him some breakfast.

This morning, though, the streets still relatively quiet, the street lamps still lit, Zeke’s mind has clearly been buzzing with activity for quite some time.

He speaks quickly, inspired:

“What if I brought a big bucket of ice up to the north? I could pour it in the water and make it all cold again!

“And when that bucket gets empty, I could bring another and another and another.”

Another idea occurs to him, “Or I could make a machine that shoots sticky snow! It could stick the snow to the other snow so that it was all one big thing again! But it wouldn’t stick to the bears! Just to snow, and the bears would have a whole big ice land for their home again!

“It could be my GREATEST INVENTION!”

My voice is thick, hoarse with sleep, and I feel genuinely sad as I say, “I wish you could fix it that way sweetie, but unfortunately the problem is much bigger than that. What will need to happen is for all of the people in the world to change the way that they live and to try and take better care of the earth.”

Zeke looks at me very seriously, his voice is world-weary (at 5) and thoughtful, “Yes. Because many people don’t care about the earth. They are selfish and they only think about themselves and their families.

They don’t realize that THE EARTH IS A LIVING THING!”

“You’re right,” I say. “It’s a very big problem and the grownups spend a lot of time arguing about what to do, when they could be trying to fix things.

Then Zeke fixes his blue eyes steadily on mine and says, with a very adult determination,

“Well, then it just might be up to the boys and girls.”

For the Boys: The Princess and the Pea

My husband and I got a rare break from the incessant demands of childcare the other night when my parents came and took my children to stay with them for an entire week. We celebrated our first night of freedom with a trip to the movies. It was hot out and we decided to go see The Heat. It was supposed to be funny and didn’t look particularly mentally taxing, which seemed to fit the bill for the evening.

We chose a theater near Union Square to catch the movie and as we walked by we saw many people gathered there.

Hundreds certainly. Thousands, maybe.

They were in a pen created by metal barriers, reinforced by a battalion of police officers who stood, hands on hips, on the other side.

We couldn’t cross the square without asking permission of an officer to go behind the barrier and then asking again to be released. The people who stood there held banners made from bedsheets and placards with slogans scrawled on pizza boxes.

They were quiet mostly. There was a feeling of mourning, mostly.

Our movie was starting soonish and we were both hungry, so, rather than cut across the square and be forced to deal with all of that, we went the long way around to find someplace where we could quickly grab a bite.

After artfully stashing my chocolate covered pretzels, Diet Coke and yogurt in my bag, we went into the theater and found seats. My husband and I engaged in our usual negotiations about what row to sit in: he going right to row 2, me to row 15; both eventually ending up together, somewhere in the middle. As always, we silently conferred about the previews, shaking our heads disapprovingly at the stinkers, exchanging raised-eyebrow glances at those that looked promising.We munched our snacks, basked in the air-conditioning, and held each other’s hands.We were ready to be care-free and to laugh at a ridiculous profanity-laden film, that we could never take our children to see.

And The Heat was funny!

The whole audience was rollicking: laughing loudly at every crazy, inappropriate thing that wackily-vested, frizzy-haired Melissa McCarthy said; guffawing whenever characters onscreen rolled their eyes at uptight Sandra Bullock with her stupid, fussily bobby-pinned hair and her tailored lady suits.

My husband was issuing these deep belly-laughs with a wet choking quality, and as I watched him wipe tears from his eyes and lean back in his seat so that he could relax more deeply into the laughter, I noticed that I was distracted, merely issuing a polite chuckle here and there.

I really wanted to laugh but for some reason, like an annoying pebble in my shoe that I just couldn’t ignore, I found myself picturing the photos printed out on paper and glued to the back of pizza boxes, the slogans painted in neon colors and outlined with sharpie, and the people who I’d seen, somberly standing in an improvised cage surrounded by uniformed officers.

I felt like a wet blanket. I was there to escape– to have fun.

So when Melissa McCarthy ripped off Sandra Bullock’s uptight trousers and knelt staring at her fastidious beige Spanx, completely aghast at the rigid little woman before her and the depth of her control issues, I tried to get into it. It was really funny. Really.

But then, there was this other scene– it’s a really funny scene–it’s in all the commercials, so you know it’s a highlight– where our girl-power buddy cops hang a perp by his ankles upside-down over a fire escape. And the perp is this young African-American man, who admittedly is a drug dealer who has information that our ladies need, but I found myself distracted again, unable to relax back into the film.

Oddly, I found myself reflecting on The Princess and the Pea.

We all remember the story:

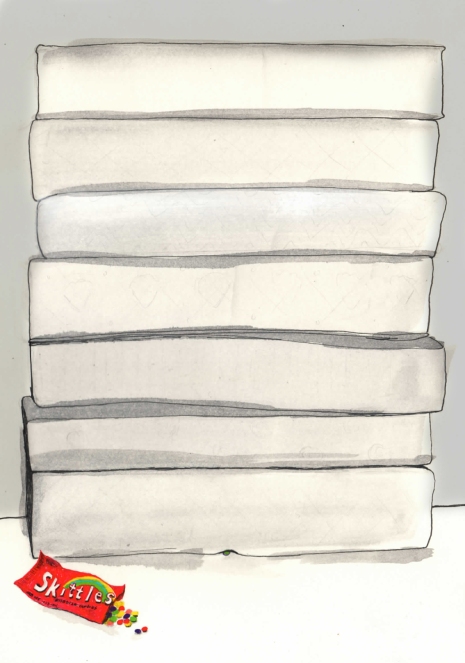

There’s this prince who is determined to marry only a “real” princess. He meets all sorts of beautiful girls but finds fault with all of them– they are not “genuine” enough for him for one reason or another. Then, in the middle of a violent storm, a bedraggled girl shows up at the palace doors, claiming to be a princess who needs shelter for the night. The Queen suspects this drowned rat must be lying, so she places a pea under twenty mattresses and twenty feather-beds and then sends the girl to bed. In the morning everyone is stunned when the girl emerges looking exhausted, and complaining of bruises on her body from some horrible lump in the luxurious bed.. She eventually admits that she was tossing and turning all night long, unable to escape the pain of whatever was under the mattress. She must be a real princess, everyone decides, for only a real princess could be sensitive enough to have detected that tiny pea.

I never liked this story. It irritated me that the ideal princess was so delicate, so over-sensitive, that she couldn’t just roll over, away from the teeny pea lump, and get some rest. She seemed like a prima-donna, annoyingly over-sensitive, just indulging herself in pointless drama.

But here I found myself, unable to just roll over and settle back into a trivial summer comedy, because I’m focused on the young man on-screen, whose humanity and civil rights are being completely disregarded (to great comic effect) by people who exploit their power and authority and take extreme measures to do what they, admittedly, passionately, feel is necessary in order to protect the community.

Every time that the audience rolls their eyes at Bullock’s namby-pamby insistence on creating a dialogue with a suspect or following protocol, I find myself shifting uncomfortably in my seat. Every time McCarthy whips out her gun to get her way and says something crazy, I find myself unable to just enjoy the film and laugh with everyone else.

And I’m annoyed with myself, because I don’t want to be that girl— the one who’s so sensitive that she can’t take a joke. But still, I find myself staring into the darkness, distracted completely by my circling thoughts, like annoying lumps in my mattress that I just can’t avoid.

I have two sons. They are 4 and 6. Just little guys.

And through being their mom, I find myself deeply enmeshed in the world of little boys and all of their exuberant “boyness”. I’ve loved watching these boys at play, watching them grow up.

I love them: the way their sturdy little legs all-of-a-sudden break into a full-on run, those soft-rounded boy bellies that mark them as our babies even as they gruffly try to be cool, even the way you can make any one of them hysterical with the barest mention of poop.

I’ve smiled at these boys on the playground, at their dimples and their scabby knees.

I’ve watched them strut around the neighborhood wearing capes.

I watch them, all of them, with their scratched plastic Spiderman figures, or race cars, or random robotninjaaliens, clutched tightly like totems as their arms swoop majestically through the air and they mutter to themselves, unself-consciously engrossed in a wild, heroic adventure.

I’ve watched their eyes shine with admiration when they watch bigger boys, boys who have skateboards, and ear buds, and heavy backpacks loaded with stuff.

And as much as they are the same, I can’t ignore this nagging, lumpy difference.

A difference that I cannot get away from, though I don’t really feel comfortable talking about it.

A difference so deeply ingrained in our culture, that it can be the unquestioned foundation for a joke.

A difference which means that my sons will grow up with a sense of safety and security and a trust in authority that will not be afforded to some of their friends.

In 8 or 10 years, some of these boys’ parents will be teaching them to walk slowly and to keep their hands out of their pockets, to speak softly and keep their eyes cast down, while my boys will still enjoy the luxurious freedom of running haphazardly down Flatbush Avenue.

And though it doesn’t feel right to spend all night lying on that lump- feeling it press into me, bruising my flesh, leaving me exhausted and in pain- it is not right to just roll over and go to sleep either.

I never wanted to be a princess and I find myself really unsure of what exactly to do now.

That Dog Won’t Hunt.

I’m walking the boys down the street just before 9 0’clock in the morning. We’re rushing to get to summer camp when we pass a planter on the corner filled with soaring green stalks sprouting cheerful blossoms that are a delightful watermelon pink. They are gorgeous and at least 6 feet tall, and when I see them I exclaim, “Look at those amazing, tall pink flowers guys! I think that they might be honeysuckle!”

I’m walking the boys down the street just before 9 0’clock in the morning. We’re rushing to get to summer camp when we pass a planter on the corner filled with soaring green stalks sprouting cheerful blossoms that are a delightful watermelon pink. They are gorgeous and at least 6 feet tall, and when I see them I exclaim, “Look at those amazing, tall pink flowers guys! I think that they might be honeysuckle!”

Both of my boys stop to admire the flowers and Jack says sadly, “Be careful! Don’t smell them! Because remember, one time, when by accident, we smelled that mean lady’s flowers?”

And all over again I have angry knots in my stomach and I want to kick my obnoxious neighbor in the teeth for ruining what used to be one of the most lovely parts of my day and suffusing, what was a sweet, calm ritual of exploration and discovery, with anxiety, mistrust, and fear.

This is for you Ridiculously Rude Resident of Rutland Road.

My kids can’t get you and your aggressive incivility out of their heads.

And it is because of you that my little boys

fear to stop and smell the roses.

Thanks a lot.

Hope you’re happy.

We live in a large apartment building right on the border of a land-marked Brooklyn neighborhood that is filled with gorgeous brownstones and free-standing houses. It is common for people in our neighborhood to have things that are uncommon elsewhere in New York City, like backyards, generous front stoops, and lovely front gardens.

Every morning when Jack and I are walking Zeke to school we wander past all of these houses and blissfully examine the beautiful new things that are growing. The three of us celebrated the coming of spring by noticing the appearance of precious little purple crocuses in so many of our neighbors’ gardens. It delighted me when my boys would point out clusters of “Happy Daffodils” or point excitedly to a vibrant yellow-blossomed bush and shout, “Look Mom! It’s forsythia! Your favorite!” We were sometimes a little late for school because the three of us had lingered too long, noses clustered together around a planting of rich indigo hyacinth, deeply inhaling their fresh, heavenly scent.

I would ache with love for Zeke when he would crouch down inquiringly before a patch of flowers, cock his head, and ask, “Are these pansies?”

And when Jack would tell me that he wanted to turn on Rogers Avenue so that we could pass by the house with the “bunches of Bleeding Hearts“, I would have to summon everything that I had inside of me not to grab his little face and smother him with kisses.

I love our morning walks, softly lit, before the sun is strong.

I love this little opportunity to delight in gracefully growing things, right here, in the middle of Brooklyn, especially when we live in a big brick building that smells more of piss and weed than it does of Lilies of the Valley.

One morning, in early June, we were taking our walk as usual. It had rained overnight and all of the plants were still moist from the light summer drizzle. The air was cool and soft. Zeke, Jack and I were admiring the way that the damp grey of the morning made the colors of the plants vivid and the way that the flowers almost sparkled when light would bounce off of a raindrop on a petal.

We turned onto Rutland Road and all three of our pairs of eyes seemed to settle on the planter at once. It was a barrel planter on the sidewalk with a small, rather spindly, rosebush inside of it, but the few roses on the bush were immaculate. The blossoms were wide and fully blooming, a striking vibrant coral.

“Those are beautiful Mom! What are they called?” Zeke asked.

“They’re roses, Sweetie,” I said. “And roses are so special because they smell absolutely amazing! Should we sniff them?”

Both boys nodded eagerly. And in our own little bubble of happy family warmth, we wandered over to the planter and leaned our noses towards the flowers, when we were jolted out of the pleasant mood by an angry shout,

“Aw Hell No! Get those kids the hell away from my flowers!”

A large, angry woman appeared at the door of the house, a phone at her ear. I was startled, but I managed to say, “Oh I’m sorry ma’am. We were just smelling them. I always tell my boys to be very gentle and not to touch.”

She continued to glare at us with profound hostility.

“Whatever. Just move on. Stop trespassing.”

I started to get really angry but I saw my children’s eyes growing wide with concern and I wanted to defuse the situation, but also to reassure them that we hadn’t done anything wrong.

I spoke up a little more forcefully, “We are not trespassing. We are on the sidewalk.”

Her lip curled as she snarled, “Stop talking! Move on and stop trespassing before I call the cops and have you arrested.”

I knew that this was ridiculous. We were standing on the sidewalk. We hadn’t even touched her property, let alone damaged it in any way. But I could see how scared my kids, who are not used to harsh language from adults, were getting and I definitely didn’t want them to see me get into a pointless argument with some obnoxious stranger. So I ushered them along, and struggled to push down the knots of seething fury I felt stirring in my gut. I wanted to focus on seeming unfazed by the situation so that Jack and Zeke could just forget about it, but moments after we walked away, the questions started.

“Why didn’t she want us to smell her flowers Mom?”

Zeke gestured toward flowers planted in front of another house.

“Is it okay to smell those?

Or those?”

He added, “Did you hate that lady, Mom? I hated her. I hated her so much. I just ignored her and thought about how much I hated her and how much I wanted her to die.”

I realized that I needed to say something, to put some sort of label on what had happened so that it could make sense to my little guys and so that they would have an idea of how to feel about the situation.

“That lady was just really mean,” I said calmly. “It is never okay to be mean to people like that, or to speak to people like that. I don’t like her, but I don’t hate her. I don’t care about her at all. She was mean and the best thing for us to do was to just walk away.”

“Were you afraid?” Jack asked sweetly.

“No I wasn’t afraid. Were you?”

“No?” he said, without much confidence.

After we dropped Zeke off at school, I tried to proceed with our walk back home as if nothing unusual had happened. But at the first hydrangea that I tried to point out, Jack said nervously, “Are we going to walk by the mean lady’s house?”

“No,” I said. “She lived on Rutland Road. This is Midwood.”

“Were you scared of her, Mom?”

“No. Of course not honey. Were you?”

“No.”

We walked on in silence. Inwardly I was cursing that woman for making it impossible to unselfconsciously enjoy our morning routine. Jack looked thoughtful as he walked.

We were almost home when he looked up at me and said, “Mom if we ever pass that mean lady again and she yells at us again, I am going to say something.”

I crouched down in front of him so that I could look into his eyes and I took both of his hands. “What would you say sweetie?”

Jack fixed his blue eyes on me seriously and spoke in a deep voice, that was clearly his childish imitation of his father when he’s frustrated by children that are acting wildly and/or irrationally:

“I would say,” he told me.

“That dog won’t hunt.”

Perception: The Apple of My Eye

Jack’s little body is heaving with sobs. He wails again and again, “How do I grow into a grown-up? How do I get bigger?” and he is breaking my heart.

I am changing his diaper. Potty-training Jack has been a monumental challenge, and he is resistant to even the slightest suggestion that he start relieving himself in the potty.

I am exhausted by the effort it takes to stick to my pro-potty talking points and disgusted by the foul mess that I must clean up day after day. In addition, I feel brutalized by Jack’s intense emotional response to the process. He wants the growing and maturing to be over, to just be “big” (and potty-trained), without having to experience the torment of growing.

Grief pours from him as he moans oddly,

“I want my eyes to be bigger. “

And that is when I pause, thinking all of a sudden of the oft-cited fact that children’s eyes reach their adult size from a very young age, some say as young as two, and that these “wide” eyes are what give children their irresistible look of innocence. But what does it mean that their adult eyes– shifting, watchful, careful not to betray intentions or vulnerability– are already there?

There’s a deli next to Zeke’s school– coffee, sandwiches, drinks– nothing to distinguish it from any other random bodega in our neighborhood, except possibly for one thing: this deli houses a scrawny gray and white cat. The cat skulks around, presumably to keep rodents from eating up the profits. And truthfully, even this doesn’t really differentiate it from other delis, except that for some reason, this scraggy, bony feline has completely captured Jack’s heart and imagination.

After we drop Zeke off at school, Jack invariably begs to go inside and look around for the cat. One day Jack asked the silent and watchful man behind the deli counter what the cat’s name was. The man stifled a snort and said in a lazy voice, “You give a name, and that will be cat’s name.”

Jack thought for a moment, then beamingly declared,

“His name is Catty-Cat.”

And from that day forward, so it was. We went to visit Catty-Cat several mornings a week and as Jack happily wandered around among the racks of chips and peeked beneath the coffee machine, I felt creepily aware of the alert gaze of the deli’s proprietors, tracking our every move.

In addition to the silent man behind the counter, there is a much chattier fellow, just a little taller than I am, the whites around his darting eyes huge and strangely bright. He dresses in an overly enthusiastic and dated “hip-hop” fashion, that calls to mind Ali-G.

He would always greet Jack with a vehement friendliness, often grabbing Catty-Cat out of whatever corner she was hiding in and roughly presenting her to Jack. His tensed hand would be positioned in front of her paws as he spoke firmly in her ear , and loudly encouraged Jack to pet her. He always insisted that she was terrified of everyone but Jack, whom she loved (attempts to spring from his firm grasp and escape from Jack’s clumsy little hands, notwithstanding).

Once he glanced pointedly at my wedding ring and asked me why I never came in with my husband, asked if he was “away in the army”.

Another time he insisted on giving Jack a free snack from the shop, and as Jack happily selected a bag of “butter-flavored” popcorn, that I knew I would never actually allow him to eat, he told me about his two children, pounding forcefully on his chest as he insisted that his son was “his heart” and that he loved him much more than his daughter.

He and his friend made me insanely nervous. I found myself trying to cross the street before we reached Catty-Cat’s deli. There was nothing I could put my finger on exactly that made me want to avoid it, but when we were there I always had a knot in the pit of my stomach, and I always kept a wary hand firmly on Jack’s shoulder as I hurried him through our visit and out to the safe anonymity of the street.

But Jack took such pleasure in visiting Catty-Cat and it was hard to resist the joy shining from his child’s eyes, as he placed his hand on her protruding ribs and felt her vibrating purr. So from time to time, we did stop in, though I did my best to be brusque and never to meet anyone’s gaze.

Then one rainy day, we stopped in and as Jack’s little voice called , “Catty-Cat? Catty-Cat where are you?” our colorful friend sauntered over to us and told us that we couldn’t see her because she was in the back room. I saw consideration wash over his face and saw the slight shift in his expression that indicated that he had actually changed his mind. “Wait,” he said. “I show you where she is.”

And as he ushered us toward the back room of the deli, I gripped Jack tightly and felt panic rising in me slightly. All of my adult instincts were telling me to be on alert, but a needling part of my mind told me that I might be being ridiculous, that this man had never been anything but friendly, and that there was no reason to deny a child an experience that made him so happy, or to make him feel nervous about people that had been kind to him and a cat that he had discovered and named. I wished that I could see it all with his innocent joy and wonder and turn off my full-grown anxiety.

In the back room we saw Catty-Cat. She was grooming herself, perched on a dingy, once-white vinyl dining room chair. Jack’s eyes locked on her with delight and I found myself nervously glancing around the room.

Next to the chair was a filthy over-flowing litter-box, and a giant hookah, as tall as Jack.

The room was surprisingly empty for a store room. There were a few cases of A & W Cream soda, a variety of mops and buckets and a metal drain in the center of the concrete floor. My eyes kept being drawn to a strange lofted platform that dominated the room. There were 3 or 4 crudely built stairs that led up to it and a neon-printed shower curtain separating it from the rest of the space. Through a gap in the curtain I could see a large duffel bag and a precisely made pallet, where someone clearly slept.

My heart and mind began to race as it dawned on me that SOMEONE LIVED BACK HERE– and I wasn’t sure if that was legitimately scary or not and I didn’t want the man to perceive that I was afraid and I didn’t want to frighten Jack, but I just wanted to get out of that room and back outside as fast as humanly possible.

As I led Jack back to our apartment I was struck by how profoundly differently we experienced that morning in the deli. Jack chattered about Catty-Cat and was aware only of the magic of this living being, that ate and breathed, and felt things, and allowed him to interact with it. My mind was possessed by paranoia and the potential for danger. Whose mind did it make sense to dwell in? The world is certainly more lovely in Jack’s eyes. And it saddens me to imagine his child’s vision being clouded by fear and mistrust.

My father studies Perception, and I remember him teaching me about the eye from a young age, quizzing me on of its various parts: the lens, the iris, the cornea, the rods and the cones. He excitedly explained that the brain fills in blanks so that we would perceive a clear and complete picture of what was before us.

It seems to me that this is very similar to what my adult view of the world does to Catty-Cat’s deli. I don’t understand what is going on in there. There are huge and petrifying gaps in my knowledge about the deli’s staff and why someone might live in the backroom and why someone might tell a stranger that they don’t really love their daughter, and without the benefit of a complete picture, all of my mental alarms go off and fill in the fuzzy areas with a strident vigilance.

Children are free to experience the unexplained, without that terror. We absorb all of the fear for them, tightly grip their little hands, and quietly scan the horizon for threats. In their yearning to grow up so quickly and to be independent, they have no idea that potty-training is merely the barest beginning of independence or of how incredibly sinister life for an adult can be.

We teach them to use the toilet, and to tie their shoes, and to navigate the world on their own.

And from us, they also learn to put their guard up. They have to. In order to survive, we all need to assess risks and think about the dangers that could be lurking in the places that we can’t see clearly.

But, in the moment, in Catty-Cat’s deli, as I gaze at the contented glow on my young son’s face while he caresses that skittish bag-of-bones, I don’t mind that soon I will go home and change another dirty diaper.

And I am acutely aware of a raw longing for the time when

I could wallow without fear in the simple rapture of an unfamiliar cat’s purr,

rather than being so keenly aware,

one hand on my son’s shoulder, one eye on the door.

The Big Ooh

Lately, every night it’s the same thing:

“Mommy, close the door,” Jack whines, “So the monsters can’t get in.”

I don’t know where this new fear has come from. I can’t put my finger on exactly when it started, or what it is that sparked it. All I know is that now it has become routine to make a show of closing the door securely so that Jack feels secure enough to relax into sleep.

I was lying in my own bed, watching the shadows of the passing cars drift across the ceiling, contemplating Jack’s new fear and whether or not it was worth being concerned about, when in a flash,

I recalled The Big Ooh.

I can still see Zeke laying in our bed, his little hands clutching the blanket tightly, where it was tucked beneath his chin, eyes wide and staring.

“Mommy,” he would say, in a whisper. “I saw The Big Ooh again.”

We live in a building that is right off of Flatbush Avenue, a busy street in Brooklyn, where it is never truly dark or completely quiet. Aaron’s bicycle hangs on a hook near the ceiling and and as the cars rush endlessly by, headlights shine over handlebars and through the spokes of the wheel, creating patterns of light and shadow, which ebb and flow endlessly past.

Zeke watched the shadowy shapes roll across the ceiling night after night, and to him they became something alive:

The Big Ooh.

He was vague on the details of The Big Ooh. He seemed less frightened by her than intrigued. He told us that she had red eyes and that he only saw her at night because during the day she was busy “taking care of her children”.

And, with a jolt, I remembered something else too.

When I was a little girl, there were these “people” that lived under my bed. I wasn’t exactly afraid of them, but I was always very aware of their presence and that awareness made me a little uneasy. I’m not sure if I ever mentioned them to anyone, but I have very vivid memories of lying awake in bed thinking about them and being almost paralyzed by my profound awareness of their presence. I remember taking deep breaths and resolving to be brave enough to hang my head over the side of my bed and peek down at them. It would take me a while to summon the courage, and my glances were always brief and breathless.

They would lie with their backs to me, their stomachs on the floor, heads propped up on their elbows. They were fuzzy and gray; shadowy. They looked as if they were made of fog and hairballs and dust. And I knew they were under there, but I also knew that they would never come out.

My memory of them is as vague as their lazy silhouettes were, but they remain one of the oddest and most exhilarating memories that I have, because my rational adult mind tells me that they couldn’t possibly have been under there. But I still remember them.

I saw them.

And I never had an “Aha” moment where I realized that my overactive imagination was spinning dust bunnies or lost socks into mysterious lethargic beings. Their presence was never explained away, and I can still remember the way they looked, the way I saw them as a child.

I have since asked Zeke about The Big Ooh and he has no memory of her at all. I suppose that whatever Jack imagines is lurking behind the door will fade away too.

And as they grow and their childhood fears disappear, so too will the world where magic is possible. Danger will be all too unavoidably real and even a door that is firmly shut will not make them feel safe.

As their mom, I desperately want to protect them from any and all danger, and to keep them safe within my tight and reassuring grasp.

But there is a part of me that wants them to hold on to the indistinct creatures of the night, somewhere deep inside, even if they can’t really believe in them anymore.

To remember that once, you believed.

That is a gift.

“I am Zeke and I Speak for the Salamanders.”

We spent some time in a small cottage in Vermont this summer. Our children shed their shirts and shoes moments after we arrived and it was a delight to watch my two Brooklyn-born boys dart about freely in all of that nature. They scampered happily through fields, amassed collections of sticks and pebbles, scaled boulders, and explored old barns.

We spent some time in a small cottage in Vermont this summer. Our children shed their shirts and shoes moments after we arrived and it was a delight to watch my two Brooklyn-born boys dart about freely in all of that nature. They scampered happily through fields, amassed collections of sticks and pebbles, scaled boulders, and explored old barns.

One evening Zeke discovered a copy of The Lorax by Dr. Suess on a shelf. It begins with a little boy exploring a barren wasteland and wondering how it came to be that way. He comes across the mysterious Once-ler, the only living being there, who tells him the story of discovering this idyllic land, once filled with adorable animals and a forest of beautiful “Truffula trees”. The Truffula trees are topped with fluffy, candy-colored foliage that the Once-ler used to knit cozy garments called Thneeds. This quickly becomes a profitable business. As the business grows, the Once-ler builds factories and chops down many, many trees, to keep up with the public’s demand for Thneeds.

As the landscape changes a small mustachioed figure called The Lorax appears, saying, “I am the Lorax and I speak for the trees.” He urges the Once-ler to care for the land so that the animals and plants can survive there. The Once-ler, who has become wildly successful, ignores the Lorax’s warnings and eventually the air and water become so polluted with waste from the factory that all of the animals are forced to leave. He short-sightedly chops down all of the Truffula trees as well, leaving his business unable to survive, and leaving him alone and broke on the land that he has decimated.

Zeke was engrossed by the story and as I read his brow creased with concern and his blue eyes grew wet and heavy. In his 4 years, he had never encountered the concepts of corporate greed, environmental devastation, or short-sighted selfishness that the story explores and again and again he asked me to explain why the Once-ler would act this way. As I read on I began to wonder if I really wanted my kind-hearted little boy to be aware of this negative side of human nature. He seemed so deeply effected by the Once-ler’s actions and by the powerlessness of the Lorax who speaks up, but can’t seem to bring about any real change.

Then we came to the conclusion of the book

The Once-ler summons the little boy closer and tells him that when the land was left uninhabitable, the Lorax picked himself up and floated away, leaving only a stone carved with the world UNLESS. He drops into the boy’s hand a tiny seed, the last of the Truffula seeds, and explains to him that UNLESS someone like him cares about things, nothing will change. He urges the boy to take care of the seed, to give it clean water and air, to protect it, and grow a new Truffula forest, so that maybe the Lorax and his friends can come back. And as I read the closing lines I could see Zeke’s mind working. He had the joyous light of hope in his eyes and my arms broke out in goose-flesh as I looked at his ecstatic expression and realized what a profound impression this book was making on him. He spent a long time flipping through it, gazing intently at the pictures, his eyes still lit with possibility.

On a sunny afternoon a few days later, we visited a nearby pond to go swimming. Aaron took Zeke out into the water, while I took Jack by the hand to explore the weeds by the edge of the pond, in the hopes of scoring a glimpse of a frog, a turtle, or a darting school of minnows.

We came across a group of children hard at work on an ambitious project. They were mostly spindly-legged boys, with sun-bleached shaggy hair, tirelessly carrying out the orders of their leader, a long-legged girl of about 12, her hair in thick brown braids. She directed them with a stern humorlessness and angry confidence that had clearly been learned from the adults in her life. She had broken her crew into two groups, each group working resolutely on the two sides of what I will call, “Project Salamander”.

The weeds by the edge of the pond were filled with little adorable, squishy, brownish-greenish salamanders who were covered in perfectly round yellow spots. Their eyes were cheerful black bulges and their mouths curved upwards into friendly smiles. If you spotted one, like a shadow beneath the water, you had to move swiftly and decisively, or it would just dematerialize and instantly find refuge somewhere in the deeper darker water.

Half of the kids were trapping and collecting the slippery salamanders in a large red sand bucket– they had nearly 20 when we arrived– while the other half were constructing a pond for them. It was about 3 feet across with thick sand walls. They filled it with pond water and artfully scattered silver-dollar sized lily-pads over the surface, presumably to make it more natural and appealing to their amphibious captives.

Jack, who declared his intention to be a zookeeper shortly after his second birthday, was immediately entranced. He watched the children excitedly and, like the boys working on the Project, he quickly grabbed a bucket and fell in line behind their leader. Under her business-like, watchful eye, Jack was allowed to pour a bucketful of water into the newly constructed pond and to hold a salamander and pet it.

“So Cue-oot!” he squealed.

When the small pond was complete the leader allowed Jack to place one hand on the red bucket as her crew transferred the salamanders to their new home. Disapproval registered instantly on her face when she examined the murky boy-made pond and the salamanders lying sluggishly at the bottom.

“NO!” she snapped. “This isn’t working! They blend right into the sand so we can barely see them! And they aren’t really moving!”She dipped an authoritative hand into the pond, “No Wonder! This water is too warm! It’s warming up too quickly! We need cold water! Now!” She snapped her fingers at one of the boys.

When the boy returned with cooler water from the large pond and poured it carefully in, a portion of the sand wall slid down into the water, further obscuring the salamanders.

“They are going to get away!” the leader shrieked furiously. “Collect them! Put them back in the bucket!” She counted them carefully as each salamander was recaptured and put back in the sand bucket.

The pond abandoned for now, she put her entire team on the job of catching more salamanders. They walked slowly and carefully into the water, holding white nets. After each step they waited for the sand to settle to keep their view of the bottom clear. When a salamander was spotted, they swooped their nets down and scooped the little fellow up before he could scoot off to freedom.

When I commented on their impressive salamander catching skills, the leader looked at me humorlessly and said,

“Where my dad lives, we spend a lot of time catching crayfish and we have become quite skilled at it. We have found that once you can easily catch a crayfish, you can catch pretty much anything without too much trouble.”

As she spoke, the boys stood carefully at attention, awaiting instruction. By now, even I was a little bit afraid of upsetting her.

As I watched this bossy, brown-eyed girl, I flashed on the camping trips that my family used to take near the New York/Pennsylvania border when I was a child. I remember supervising my younger brother and sister as we scoured the forest floor, searching for these sweet little newts that were a bright, story-book illustration tangerine. We too would collect them in buckets, which we lined with grass and sticks to make perfect little habitats for them, where we imagined they would live contentedly as our pampered pets. I clearly remember how I would love them fiercely for an afternoon, or until something else caught my fancy.

So, I was quite taken by Project Salamander. I desperately wanted to pick up the salamanders and cuddle and kiss them too, but being the adult, I felt that it was more appropriate to insist upon my children acknowledging how amazing they were.

The boys’ cousin Nathan was with us at the pond and I lured him over to the bucket with an enthusiastic awed voice that never fails to pique childish interest.

Next I moved to Zeke:

“Come here Zeke! This is SO COOL! Look at what these kids have been doing! They caught all of these salamanders and they are so cute!You won’t even believe it!”

Zeke walked over and looked down into the bucket. Immediately his eyes went dead and in an strange thoughtless sort of move, like that of a toddler with a random destructive impulse, Zeke began to tip over the bucket. A chorus of “NOOOOO” rang out all around us and someone picked up Zeke who was kicking and yelling in a desperate fury,

“No! NO! They don’t have enough room in there!

They need the whole land!”

And my confusion at Zeke’s odd effort to ruin the children’s project disappeared as I saw his deep compassion and his furious passion. In that moment, Zeke was the Lorax and he saw beyond the charming amusement of a group of children, to the suffering of the confined salamanders, who deserved absolute freedom in the vast, cool, deep water that was their home.

As we prepared to leave our Vermont cottage, an impressively violent thunderstorm materialized. Thunder shook our little cottage. Lightening flashed across the sky and rain pounded the fields. Zeke and I were inside, finishing up the packing, while Aaron and Jack took out the garbage and got our truck.

“Oh no!” I said. “It’s raining. Do you think Daddy and Jack are getting all wet?”

My little Lorax smiled at me, and said:

“It’s okay mom. I love it when it rains. It keeps the earth healthy.”

And I remember smiling back at him, a great looping love in my heart, as I held his warm little hand and we looked out together at the staggering power of the storm.